By Anna Snader

The hot May sun shines on my college travel group as we wander Hiroshima’s quiet side streets. We have flown across the Pacific Ocean, ridden in futuristic bullet trains, and walked miles of sidewalks to be here—to learn about culture, about perspective, about truth. Today, we are in search of the hypocenter, the place where the Americans dropped the bomb on August 6th, 1945—the explosion that split the sky and shredded a city into paper shavings. The explosion a thousand degrees warmer than today.

We finally locate the memorial, which is isolated from the crowded shopping district. Before us stands a flat, brown sign with information about the bomb—how hot, how high, how horrible. I stare at the gleaming sign, the newness plastered over a place that holds the devastation of a world torn apart.

We will walk away from the hypocenter, like all Americans do. I want to glance behind me.

But we are moving on.

We emerge from the city streets into the Peace Park, arriving at Genbaku Dome, a dilapidated building with empty windows, chipped cement bricks, and a skeletal rotunda. The only building that survived the bombing. I watch people stand and pose, and my professor urges us to stand there too. I say no, and turn to stare at the building again. I cannot, I will not cover up the devastation behind me with a mask of pearly white teeth.

Adjacent to the dome’s protective metal fence is a giant tree that shades the walkway. The thick branches twist and stretch out like veins, pulsing nitrogen and phosphorus into the green foliage. The tree likely didn’t live through the bombing. People probably planted it after, in that radioactive soil, as a sign that things can grow in tragedy.

But I don’t know.

We turn away, walking toward the bridge where eternal fire and thousands of paper cranes lie on the other side. Before I cross over, I stare out over the river to see the skyscrapers of Hiroshima. I imagine a mushroom cloud filling the blood-red sky. Skin bubbling on arms. Plants shriveling into ashes. Birds shrieking. A world burning.

I feel the hotness of the flame—the tomorrows and futures and dreams drifting away as I fall deeper into unconsciousness—and an ache like a searing knife. It splits my heart open, bleeding a sticky red river down the incinerated streets.

I snap back to the present. Today, the sky is blue. The people stroll along the river, only threatened by sunburn. The plants are vibrant and lush. And I am not dead.

But there are no birds in the sky, and I wonder when they will return.

***

***

I enter the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum—a long hallway filled with love letters and pictures of men with bubbling black burns. The light from outside dwindles and visitor shadows are cast on the wall, dancing with the ghosts of dead children and babies—all the lives mutilated by war. I trudge down the narrow hallways until I stand before a black and white mural-length picture.

I freeze.

It is Noboricho Elementary School, located almost a mile away from the Hiroshima bombing. Two rows of children stand in front of the school, and a row stands in the wooden window frames behind them. The girls have short bobs with pin-straight bangs and the boys wear captain hats as if they are about to sail the seven great seas. They look relaxed, with their arms hanging over the railing or around each other. Their faces break into wide grins and their eyes dance. And they are laughing. I want to be with them, laugh too.

I stand there for minutes, unable to tear my eyes away from their carefree smiles under that flash of light. Maybe this picture was special to them, an opportunity to be seen. Maybe this moment changed them, freezing time and capturing their beauty. Maybe they knew life was fragile, smiling to prove that anyone could love their life. Maybe they knew these things, or maybe, they were just kids.

Kids who had no idea what was coming.

***

Two weeks before we visit Hiroshima, we are lining up in front of the International Language House with the 35 energetic kindergarteners in yellow and blue shirts. The teachers miraculously do this within a minute. We hold our smiles and peace signs as they count off for the picture. We begin to laugh.

That morning, when we hiked up the steep Yokohama streets, a sign with a large, crooked smiley face welcomed us, along with a recent Hope College graduate who now taught there. We were immediately thrown into the daily activities. As a group, we sat in a circle and sang Fruit Basket, the jingle of “Fruit Basket, Fruit Basket….” rattling in my head all day. Later when they played in the sandbox, I watched them shovel wet, gravelly sand into a mountain, using a small shovel to carve a tunnel.

A place to escape. Or hide.

During lunch, we all sat in small chairs, and I watched them eat their perfectly-packed bentos of grapes and rice balls with training chopsticks. I tried to talk with them about their lives since I blended in with my yellow rain jacket, but they simply giggled at each other before reading their Japanese children’s books. When the chairs were being cleared, one kid sobbed after being knocked in the head. A teacher came by, said she was sorry he was hurt and hugged him to balm the pain. In a side room, the other children were sitting on the ground and laughing at their 10-minute episode of Bluey, which they watched to learn English.

Later, they went back outside to kick footballs, chase each other, and jump on the playground. The quiet Yokohama neighborhood was filled with screaming, laughing, and thudding feet. As they played, no adult hovered above them or feared for their safety like the teachers did in American preschools. The children were birds with unclipped wings—free and innocent and playful. I think of myself as a child, running and falling and skidding. Unafraid and always in love with the world.

I am pulled back to the present, to our picture. The countdown begins, and we giggle and smile with the children. They chatter in Japanese, their voices sweet and chipper. I don’t know the meaning of their words, why they are laughing, why we laugh with them. But maybe, knowing why doesn’t matter. Maybe I should smile because I can. Because I love my life. Because I am not dying.

***

On our fourth day in Japan, we take an hour-long commuter train to the small, seaside town of Kamakura to visit the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine and Engakuji Buddhist Temple. When we exit the semi-crowded train onto the quiet platform, I feel at home.

At the Tsurugaoka Hachimangu Shrine, we stroll in the shade to escape the brutal heat. I trail behind our tour guide, Yukiko-san, a small elderly woman with a cute pixie haircut. By the giant water lilies, a small girl and boy pass us in colorful kimonos, skipping up the steps toward the shrine.

We smile at their professionalism, how cute they are dressed as small versions of who they will become. Yukiko-san explains this as an important Japanese rite of passage. “When a boy is five and a girl is three and seven, their parents take them to the shrine to thank the gods for their protection. People go to the Shinto shrines for their celebrations of life like that wedding we just passed.”

I imagine the girl and boy again, growing up, getting old. They will wear their best kimonos, ladle purifying water over their hands, and hike those steps to the shiny, red columns at the summit. They will make this climb their whole life so they can bow, clap, and throw in a copper goen—their wish for luck. Their wish to be protected from the sickly skies of their country’s past.

***

***

I continue down the museum hall crowded with people and grief. I wait for the long line to move forward, until suddenly, I am directly before other solemn faces—passport-size photos of children who died during the bombing. I spot a girl with bangs, her name and age written in small print. Her name blurs in my head, but I remember her age: 14. A girl who probably played at school and gossiped with her friends and journaled stories. A girl who had friends, siblings, and parents—people who loved and searched for her among the rows of burnt bodies. This is assuming they lived, which is unlikely.

I look at her now.

She is gone, a girl who had no chance, no future.

I have met her only once, at this moment. We are countries, decades, lifetimes apart, yet I miss her like I have known her my whole life.

This ache of the unknown is an ache I have always known.

***

Halfway through my time in Japan, I pass a flock of first graders on my usual Tokyo running loop. They march the streets with short, intentional steps and waddle over the crosswalk. They are adorned in bright yellow bucket hats and backpacks so they do not get lost. So people around them know they are children who don’t know any better. And who need to be protected.

***

At the Engakuji Temple in Kamakura, I observe the tender wildness—the light filtering through maple trees, green moss sprawling over rocks, purple iris flowers floating over koi fish, and a magnificent view of the shimmering Sagami Bay. We hike the large, stone steps and spot miniature statues on a bed of soft, spongy moss. Wide smiles and squinting eyes are chiseled into their faces like lips painted on toys. They are cute and happy and strange.

Our tour stops at a plateau covered in green Japanese maple leaves. There is a small temple, and an army of tiny stone statues awaiting us. Their smooth, round heads are bowed in prayer, their eyes closed as if asleep. Yukiko-san says they are jizo—the lost children—dead from miscarriages, stillbirths, war. They are lost from this world, but await another.

I stare at the statues and listen to the gurgling stream before them. Yukiko-san says the journey of the dead children is a difficult one. They swim with the burden of leaving, of failing to live. The parents visit the temple to make their children’s journey easier. I watch as mothers enter the small temple to light incense, praying that their lost children will travel safely across a turbulent river. I think back to the small smiling figures on the bright moss—jizo who wait on paths and temple rocks, guarding the living travelers on their journeys. Until their time comes when they are consumed by oxygen-fueled flames, incinerated into ashes, and are left to drift in the winds of other worlds. As the jizo burn and die in this place between life and death, they are finally crossing the river. Arriving on some distant shore.

***

***

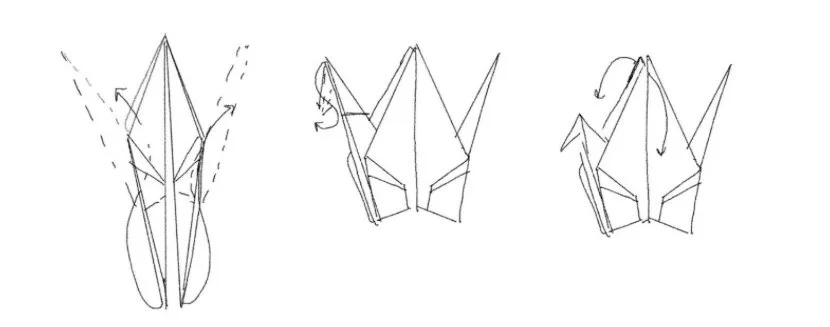

After exiting the dark museum, we pass the Children’s Peace Monument, an upside-down tulip structure with a girl lifting up a wire paper crane. As we pass, Japanese schoolchildren pay their respects. They wander and visit with the lost children. To see that this could happen to anyone. Even you.

Behind the monument are nine glass exhibition cases, overflowing with color. When I walk closer, the clear displays are packed with paper crane chains, coming from all places in all sizes and colors. When I look closer, I see they are all tied together by a singular string.

In each box, cranes are glued to the glass to form pictures of rainbows, cranes, and peace messages. Behind the window are chains of baby cranes, so small and precise, they were likely folded by tiny hands. In the next viewing box, there are rainbow chains containing every shade, running from light pink to deep purple. A rainbow, like God's promise to Noah.

The promise that destruction like that would never happen again.

***

One week before we take a bullet train to Hiroshima, my college group attends a Japanese public school to experience the difference between Japanese and U.S. education. I sit in the middle of a fifth-grade classroom, watching kids present their favorite foods, sports, and Japanese destinations in English. The kids here are boisterous and friendly and happy, asking me direct questions like “Do you like dogs?” I respond with my limited Japanese, “Hai!”

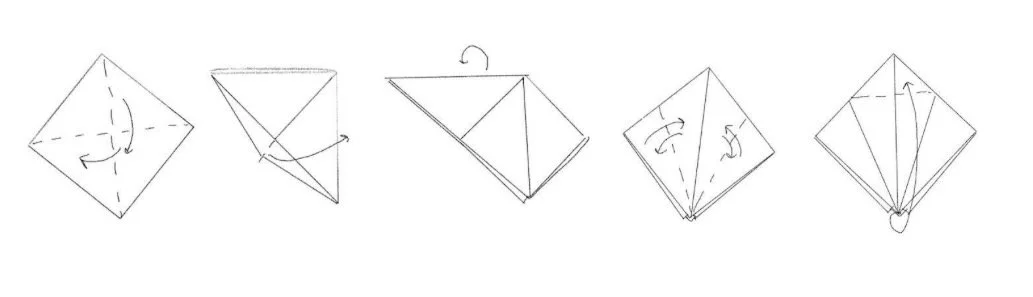

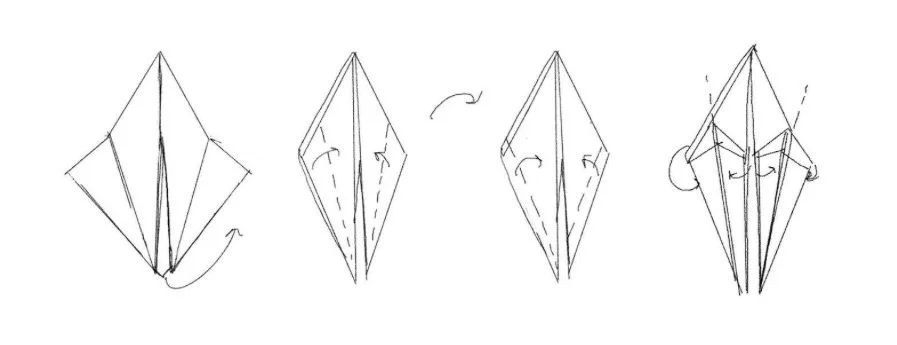

When the lunch dishes are rolled into the rooms, the kids on lunch duty don their aprons and chef hats, while the other children gather around me. As we eat, the room overflows with overlapping chatter, and peaks when the extra rice and milk is auctioned off with a number game. As I prepare to leave, the children pile all their origami—a blue paper crane, a 3-D star, a spinning top, a twelve-petaled flower, a few ninja stars—onto my table, and I cradle their creations in my arms. They trail me out of the classroom, and whisper amongst each other. When I rejoin my group in a conference room, the children stick their heads into the door and wave at us. I smile at their cheery faces. I place the twelve pieces of origami on the table, observing the neatness of their handiwork. I organize them in my drawstring bag, making sure the crisp edges are not crushed.

***

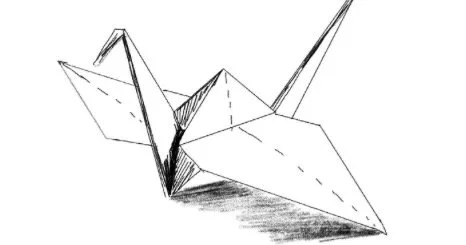

Way back in my own fifth-grade English class, I had tucked myself in the class library of three overflowing bookshelves. I searched for an independent reading book and came across Sadako and a Thousand Paper Cranes, a novel about a girl who developed leukemia after the atomic bomb, and folded crane after crane, hoping she would heal. I picked it up, unaware that my heart would break, that one day I would see the very place the world now remembers Sadako.

Now I am in that very museum, following a silent and solemn crowd that is afraid of waking the dead. I try to peer at the glass displays of Sadako’s story, but a dry itchiness crawls up my throat and I can’t keep it down. It erupts out of me, and I run.

Sadako was a real girl who folded hundreds of cranes, hoping she would live, hoping there would be peace. She died, and yet, the folding never stopped. Even now, the cranes are everywhere. I envision all the mothers, fathers, and children with their kami, folding and creasing their grief into a thousand fragile wings—those wings that would turn into wishes that Sadako would live, wishes that no more bombs would explode in the sky.

They wish, I hope, we pray that our thoughts will reach those children, that their drifting ashes will always remain alive.

***

***

I get up early to run. I want to see the Peace Park again, even though it’s raining when I exit my pitch-black hotel room. There are no birds in the gray sky, only heavy droplets that pour into a river that once witnessed an explosion that tore a city apart like the flesh of its children. I run till I am out of breath, till my limbs feel tired from pounding the cement, till I arrive, soaking wet, at a place that holds grief like radiation in bodies. I stare at the skeletal dome and the beautiful tree that breathes life into the sky, those things that remained behind.

I don’t turn away.

When I cross the river to the other side, the chains of cranes are dry under their clear glass display. I peer through, thinking of the children at Noboricho Elementary School, in Yokohama, and in Tokyo, remembering their joy and laughter folded forever into fragile paper. The delicate wings flapping in the blue sky as if whispering, Fly away. You will never be lost.

I am reminded of my red paper crane at home, which I had folded at the Holland International Festival. I stood at my college’s cultural booth and followed the instructional handout, creasing the thin paper until the beak was misaligned and its wings were slightly disheveled. I held the bird with delicateness and love, perching it on my unlit Tennessee Homesick candle—a place where it will always fly alone. Ever since, I have carried that crane in my mind, in my heart. I am not Japanese, but I have folded and memorialized those red paper wings for my own sake. Because in a country neighboring Japan, across the East China Sea, with its own violence, I am another lost child.

On the train back to Tokyo, the clouds, the children, and the cranes of Hiroshima linger over me like the absence I have always known. I ache, even though I live across the Pacific in clean air, far away from being crushed or blistered by the inferno of atomic warfare. Yes, I am breathing, and yet, I wonder if those in my homeland consider me dead. I wonder if my Chinese mother—instead of keeping a little stone baby or folding cranes—sweeps a marble grave, burns sticks of incense, or flies a fluttering kite to remember her lost daughter. A child who didn’t burn under a blood-red sky, but burned all the same.

Maybe. But I don’t know.

I simply see those delicate and fragile wings beating like a heart, urging all the lost children onward.

Hoping we cross the river.

Anna Snader is a creative nonfiction writer from Nashville, TN. Currently she studies English literature, political science, and creative writing at Hope College. In the future, she hopes to teach writing and literature. This is her first publication.